Welcome to our store

There is a growing chorus of voices in Australia’s fashion and political sectors speaking urgently about the need to revive local manufacturing, particularly in the clothing industry, with terms like “sovereign supply chains,” “reshoring,” and “domestic capability” echoing across government announcements, sustainability panels, and fashion week press releases. But despite all this rhetorical momentum, despite the roundtables, think tanks, and procurement strategies, the simple truth remains: for small businesses in the fashion industry, especially those working in technically demanding categories like lingerie, there is no real infrastructure in Australia today that allows creative, lightweight manufacturing to happen at scale, at speed, or with any economic logic.

Because while everyone is talking about local manufacturing, no one is actually building it.

When you peel away the idealistic language and look at what it means to produce a 30-piece lingerie capsule in Australia today, you quickly find yourself inside a structural vacuum. Factories that still operate are mostly set up for uniforms or basic CMT orders, with machinery designed for repetition rather than variation. Workers trained in advanced textile handling, micro-detail finishing, or lingerie construction are rare, aging, and without successors. There is no national apprenticeship system in place that understands or serves the needs of intimate apparel, no targeted TAFE program that teaches the nuanced interface between digital pattern cutting and manual fabric assembly, no industry pathway that supports the kind of iterative prototyping needed by small fashion designers.

Meanwhile, funding programs are either aimed at large-scale industrial players or focused entirely on upstream green metrics, like carbon accounting and post-consumer waste, without addressing how and where clothes are actually made. Initiatives like Seamless Clothing Stewardship may help garments die better, but they do nothing to help them be born in Australia to begin with.

To create a real future for Australian clothing manufacturing, we must move beyond symbolism and into systems-building. And systems require specific, sometimes unglamorous, action. For example, we must explore the introduction of targeted skilled migration programs, focused not on generic machinists but on patternmakers, lingerie engineers, fabric testers, fit technicians, and multi-skilled generalists trained in small-run production environments. These roles are often overlooked by national visa categories, yet they are essential to rebuild the technical base for contemporary lingerie and streetwear production.

Simultaneously, we must establish a more robust technical education ecosystem, ideally in partnership with TAFE and advanced design schools, where the traditional divide between "creative" and "technical" is dissolved in favor of integrated, iterative, real-industry problem solving. A lingerie designer should be trained to understand tension ratios and stitch compatibility; a machinist should be taught how to work with laser-cut silk blends and irregular elastic binding. This isn’t a luxury — it’s a prerequisite for future-ready, sexy lingerie production.

Australia must also consider investing in distributed micro-manufacturing hubs. Rather than rebuilding centralized garment factories that will never compete with Asia on price, we could develop regional studios with shared digital cutting tables, modular sewing setups, AI-assisted fit validation, and trained studio managers capable of running 10–20 unit micro-batches for multiple brands simultaneously. These hubs could serve as hybrid spaces for education, production, and material testing — accessible to small designers and scalable for independent labels who are otherwise locked out of meaningful production access.

If we truly want to empower small fashion brands, independent lingerie designers, and emerging streetwear labels in Australia, we must stop confusing headlines for infrastructure. We must stop measuring domestic industry progress by the number of media appearances or pilot program PDFs, and start measuring it by tangible changes: number of machines installed, number of workers trained, number of units produced below MOQ thresholds, number of businesses able to launch without going offshore.

Because at present, local manufacturing is a theory. It is a concept invoked at conferences and roundtables, but not something that can be readily accessed by most of the people who are actually trying to build the future of Australian fashion. And without creative manufacturing systems, sustainable production pathways, micro-batch sampling labs, and technical education frameworks, that future will remain hypothetical.

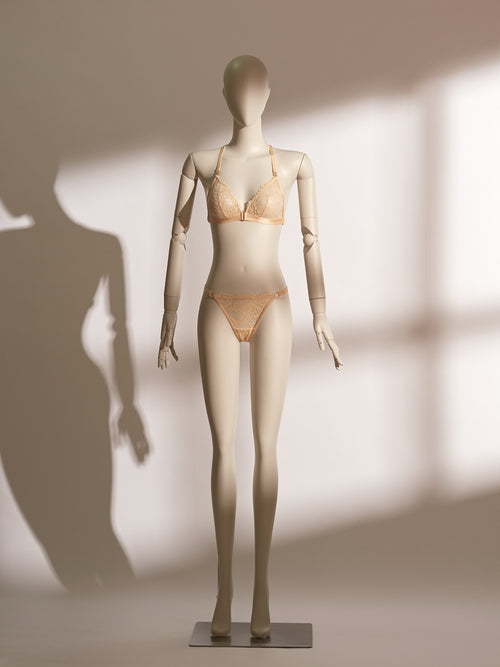

At Mismuse, we know how much technical skill, fabric fluency, and creative problem-solving it takes to bring a lingerie design to life. We understand the importance of global collaboration, but we also believe that Australia deserves the infrastructure to make beautiful, expressive, and ethically intelligent fashion at home. And we will continue to advocate for a system that rewards not just scale or heritage, but precision, experimentation, and purpose.

If you believe that fashion should be made with intention, and want to see how a modern lingerie brand is navigating design, production, and global creativity, we invite you to explore our world. Visit our homepage to learn more.